The Sun vs. “The Stars”

Glenn Gould is “the musician’s musician.” That is to say, he appeals to those who wish, for purposes of their own egos, that being an attention-getting performer — a “star” — were equivalent to, or even definitive of, being a great artist.

Murray Perahia, to take one obvious contrasting example, is the composer’s musician. He appeals to those attuned to the spirit of a genuine great artist who wishes to have his work represented sincerely, meaning without distracting competition from the ego of an ephemeral “star.”

Many moons ago, during my neo-Straussian phase in graduate school, I read Stanley Rosen’s The Question of Being, an opaque but fascinating musing aimed straight at the myth of Martin Heidegger as great philosopher. Along the way, Rosen summarizes his critique of Heidegger’s famous Nietzsche lectures with the plainly stated charge that Heidegger gets Nietzsche wrong. When I mentioned this at the time to a fellow doctoral student who was immersed in twentieth century phenomenology, his sharp response was, “I didn’t think he was trying to get Nietzsche right.”

Something like my friend’s defense of Heidegger seems to be the standard apology offered by admirers (or “fans,” more properly stated) of “the great Gould” as well: “He wasn’t trying to get Bach right.”

But what may be a fair defense of a phenomenologist’s creative interpretation of another philosopher strikes me as an absurd stretch in defending a classical pianist’s willing and iconoclastic distortions of a master composer. If this sort of self-promoting idiosyncrasy is so valuable, then at least, as a matter of pride and good taste, Gould’s beloved recordings ought not to be named The Well-Tempered Clavier and The Goldberg Variations, but perhaps Gould Riffs on Bach, or The Gould-berg Variations. (And given the ridiculous speeds at which he typically played these works, perhaps we could also repackage the recordings as Hooked on Bach!)

And then there is Gould’s infamous hum, his noisy singing along with the music he is playing. Duke Ellington did that. So did Dave Brubeck and Thelonious Monk. Oscar Peterson, too. Notice anything there? They were all jazz pianists, improvisers and stylists by definition, often playing their own melodies, or openly reworking the tunes of other composers to be used as mere frameworks for their spontaneous quasi-compositional explorations. That is the nature and essence of jazz, and none of these men, when they played the tunes of other writers, ever tried to stake a claim to having displaced the original tune in the musical repertoire, or to having supplanted anyone else’s interpretation of the same tune as the definitive one. They hummed along because they were inventing something on the fly and trying, in effect, to work it out in their heads as they played. Their humming voices became part of the charm of their music, because it really was part of their music.

Gould, on the contrary, simply lacked the classical performer’s mental discipline and “professionalism” (i.e., the studied humility) to shut up — vocally, and also pianistically, as it were — and let the composer do the singing.

But Gould’s admirers love him, essentially for all the very reasons I have just adduced against his public performance style. (What a musician does for fun privately, in his living room, is his business.) They adore him precisely for being iconoclastic, for shining his garishly personal light on other men’s masterworks, for scratching out the great composers’ directions and tempo indications in order to play Bach the way he likes it to sound — which, of course, means unlike the way it sounds when anyone else plays it. That is, he is solely concerned with looking original and unique — being a “star” — rather than with doing justice to the lingering spiritual emanations of a long-dead composer, which is what you would think a serious musician, but one who lacked such compositional gifts himself, would want to do. You would think, in other words, that a professional, recording interpreter of a past master’s music would have enough respect and appreciation for that master — his master — to want to “get him right,” for the benefit and spiritual ennoblement of today’s audiences.

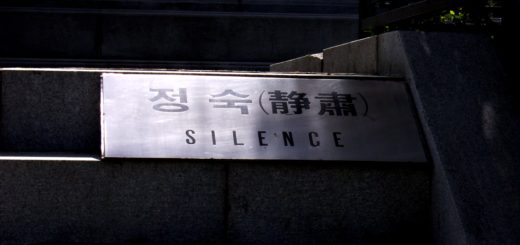

Glenn Gould embodies so much of what is small and weak about late modernity — in art, thought, politics, everything. We live off the fumes of our superiors from the past, even while spitting on their greatness in the name of elevating our tiny selves, artificially inflating our insecure, time-bound egos until they effectively block out the eternal sun that was meant to be the primary source of our energy, and the food of our growth. Our “individuality” and “personality” amount to nothing but a constant, annoying din that steals the silence from the ethereal voices that have truly earned a hearing, and that we must hear.

As a pleasant reminder of how a public performer may dutifully honor the artist he is representing, while still finding plenty of room for his own voice within his representation, here is the aforementioned Murray Perahia, offering his insights on playing Bach, in every word implicitly rejecting the song and dance routine — the sweat act — that is Gould’s Bach.